1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

|

# Contributing Quick Start

Rust Analyzer is an ordinary Rust project, which is organized as a Cargo

workspace, builds on stable and doesn't depend on C libraries. So, just

```

$ cargo test

```

should be enough to get you started!

To learn more about how rust-analyzer works, see

[./architecture.md](./architecture.md) document.

We also publish rustdoc docs to pages:

https://rust-analyzer.github.io/rust-analyzer/ide/

Various organizational and process issues are discussed in this document.

# Getting in Touch

Rust Analyzer is a part of [RLS-2.0 working

group](https://github.com/rust-lang/compiler-team/tree/6a769c13656c0a6959ebc09e7b1f7c09b86fb9c0/working-groups/rls-2.0).

Discussion happens in this Zulip stream:

https://rust-lang.zulipchat.com/#narrow/stream/185405-t-compiler.2Fwg-rls-2.2E0

# Issue Labels

* [good-first-issue](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/labels/good%20first%20issue)

are good issues to get into the project.

* [E-has-instructions](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/issues?q=is%3Aopen+is%3Aissue+label%3AE-has-instructions)

issues have links to the code in question and tests.

* [E-easy](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/issues?q=is%3Aopen+is%3Aissue+label%3AE-easy),

[E-medium](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/issues?q=is%3Aopen+is%3Aissue+label%3AE-medium),

[E-hard](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/issues?q=is%3Aopen+is%3Aissue+label%3AE-hard),

[E-unknown](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/issues?q=is%3Aopen+is%3Aissue+label%3AE-unknown),

labels are *estimates* for how hard would be to write a fix. Each triaged issue should have one of these labels.

* [S-actionable](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/issues?q=is%3Aopen+is%3Aissue+label%3AS-actionable) and

[S-unactionable](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/issues?q=is%3Aopen+is%3Aissue+label%3AS-unactionable)

specify if there are concrete steps to resolve or advance an issue. Roughly, actionable issues need only work to be fixed,

while unactionable ones are effectively wont-fix. Each triaged issue should have one of these labels.

* [fun](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer/issues?q=is%3Aopen+is%3Aissue+label%3Afun)

is for cool, but probably hard stuff.

# CI

We use GitHub Actions for CI. Most of the things, including formatting, are checked by

`cargo test` so, if `cargo test` passes locally, that's a good sign that CI will

be green as well. The only exception is that some long-running tests are skipped locally by default.

Use `env RUN_SLOW_TESTS=1 cargo test` to run the full suite.

We use bors-ng to enforce the [not rocket science](https://graydon2.dreamwidth.org/1597.html) rule.

You can run `cargo xtask install-pre-commit-hook` to install git-hook to run rustfmt on commit.

# Launching rust-analyzer

Debugging the language server can be tricky.

LSP is rather chatty, so driving it from the command line is not really feasible, driving it via VS Code requires interacting with two processes.

For this reason, the best way to see how rust-analyzer works is to find a relevant test and execute it.

VS Code & Emacs include an action for running a single test.

Launching a VS Code instance with a locally built language server is also possible.

There's **"Run Extension (Debug Build)"** launch configuration for this in VS Code.

In general, I use one of the following workflows for fixing bugs and implementing features:

If the problem concerns only internal parts of rust-analyzer (i.e. I don't need to touch the `rust-analyzer` crate or TypeScript code), there is a unit-test for it.

So, I use **Rust Analyzer: Run** action in VS Code to run this single test, and then just do printf-driven development/debugging.

As a sanity check after I'm done, I use `cargo xtask install --server` and **Reload Window** action in VS Code to verify that the thing works as I expect.

If the problem concerns only the VS Code extension, I use **Run Installed Extension** launch configuration from `launch.json`.

Notably, this uses the usual `rust-analyzer` binary from `PATH`.

For this, it is important to have the following in your `settings.json` file:

```json

{

"rust-analyzer.server.path": "rust-analyzer"

}

```

After I am done with the fix, I use `cargo xtask install --client` to try the new extension for real.

If I need to fix something in the `rust-analyzer` crate, I feel sad because it's on the boundary between the two processes, and working there is slow.

I usually just `cargo xtask install --server` and poke changes from my live environment.

Note that this uses `--release`, which is usually faster overall, because loading stdlib into debug version of rust-analyzer takes a lot of time.

To speed things up, sometimes I open a temporary hello-world project which has `"rust-analyzer.withSysroot": false` in `.code/settings.json`.

This flag causes rust-analyzer to skip loading the sysroot, which greatly reduces the amount of things rust-analyzer needs to do, and makes printf's more useful.

Note that you should only use the `eprint!` family of macros for debugging: stdout is used for LSP communication, and `print!` would break it.

If I need to fix something simultaneously in the server and in the client, I feel even more sad.

I don't have a specific workflow for this case.

Additionally, I use `cargo run --release -p rust-analyzer -- analysis-stats path/to/some/rust/crate` to run a batch analysis.

This is primarily useful for performance optimizations, or for bug minimization.

## Parser Tests

Tests for the parser (`parser`) live in the `syntax` crate (see `test_data` directory).

There are two kinds of tests:

* Manually written test cases in `parser/ok` and `parser/err`

* "Inline" tests in `parser/inline` (these are generated) from comments in `parser` crate.

The purpose of inline tests is not to achieve full coverage by test cases, but to explain to the reader of the code what each particular `if` and `match` is responsible for.

If you are tempted to add a large inline test, it might be a good idea to leave only the simplest example in place, and move the test to a manual `parser/ok` test.

To update test data, run with `UPDATE_EXPECT` variable:

```bash

env UPDATE_EXPECT=1 cargo qt

```

After adding a new inline test you need to run `cargo xtest codegen` and also update the test data as described above.

## TypeScript Tests

If you change files under `editors/code` and would like to run the tests and linter, install npm and run:

```bash

cd editors/code

npm ci

npm run lint

```

# Code organization

All Rust code lives in the `crates` top-level directory, and is organized as a single Cargo workspace.

The `editors` top-level directory contains code for integrating with editors.

Currently, it contains the plugin for VS Code (in TypeScript).

The `docs` top-level directory contains both developer and user documentation.

We have some automation infra in Rust in the `xtask` package.

It contains stuff like formatting checking, code generation and powers `cargo xtask install`.

The latter syntax is achieved with the help of cargo aliases (see `.cargo` directory).

# Architecture Invariants

This section tries to document high-level design constraints, which are not

always obvious from the low-level code.

## Incomplete syntax trees

Syntax trees are by design incomplete and do not enforce well-formedness.

If an AST method returns an `Option`, it *can* be `None` at runtime, even if this is forbidden by the grammar.

## LSP independence

rust-analyzer is independent from LSP.

It provides features for a hypothetical perfect Rust-specific IDE client.

Internal representations are lowered to LSP in the `rust-analyzer` crate (the only crate which is allowed to use LSP types).

## IDE/Compiler split

There's a semi-hard split between "compiler" and "IDE", at the `hir` crate.

Compiler derives new facts about source code.

It explicitly acknowledges that not all info is available (i.e. you can't look at types during name resolution).

IDE assumes that all information is available at all times.

IDE should use only types from `hir`, and should not depend on the underling compiler types.

`hir` is a facade.

## IDE API

The main IDE crate (`ide`) uses "Plain Old Data" for the API.

Rather than talking in definitions and references, it talks in Strings and textual offsets.

In general, API is centered around UI concerns -- the result of the call is what the user sees in the editor, and not what the compiler sees underneath.

The results are 100% Rust specific though.

Shout outs to LSP developers for popularizing the idea that "UI" is a good place to draw a boundary at.

## LSP is stateless

The protocol is implemented in the mostly stateless way.

A good mental model is HTTP, which doesn't store per-client state, and instead relies on devices like cookies to maintain an illusion of state.

If some action requires multi-step protocol, each step should be self-contained.

A good example here is code action resolving process.

TO display the lightbulb, we compute the list of code actions without computing edits.

Figuring out the edit is done in a separate `codeAction/resolve` call.

Rather than storing some `lazy_edit: Box<dyn FnOnce() -> Edit>` somewhere, we use a string ID of action to re-compute the list of actions during the resolve process.

(See [this post](https://rust-analyzer.github.io/blog/2020/09/28/how-to-make-a-light-bulb.html) for more details.)

The benefit here is that, generally speaking, the state of the world might change between `codeAction` and `codeAction` resolve requests, so any closure we store might become invalid.

While we don't currently implement any complicated refactors with complex GUI, I imagine we'd use the same techniques for refactors.

After clicking each "Next" button during refactor, the client would send all the info which server needs to re-recreate the context from scratch.

## CI

CI does not test rust-analyzer, CI is a core part of rust-analyzer, and is maintained with above average standard of quality.

CI is reproducible -- it can only be broken by changes to files in this repository, any dependence on externalities is a bug.

# Code Style & Review Process

Do see [./style.md](./style.md).

# Logging

Logging is done by both rust-analyzer and VS Code, so it might be tricky to

figure out where logs go.

Inside rust-analyzer, we use the standard `log` crate for logging, and

`env_logger` for logging frontend. By default, log goes to stderr, but the

stderr itself is processed by VS Code.

To see stderr in the running VS Code instance, go to the "Output" tab of the

panel and select `rust-analyzer`. This shows `eprintln!` as well. Note that

`stdout` is used for the actual protocol, so `println!` will break things.

To log all communication between the server and the client, there are two choices:

* you can log on the server side, by running something like

```

env RA_LOG=gen_lsp_server=trace code .

```

* you can log on the client side, by enabling `"rust-analyzer.trace.server":

"verbose"` workspace setting. These logs are shown in a separate tab in the

output and could be used with LSP inspector. Kudos to

[@DJMcNab](https://github.com/DJMcNab) for setting this awesome infra up!

There are also two VS Code commands which might be of interest:

* `Rust Analyzer: Status` shows some memory-usage statistics.

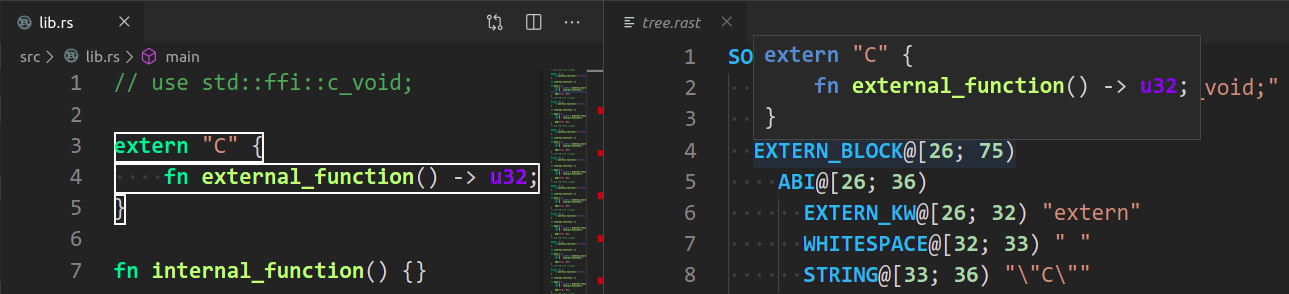

* `Rust Analyzer: Syntax Tree` shows syntax tree of the current file/selection.

* `Rust Analyzer: View Hir` shows the HIR expressions within the function containing the cursor.

You can hover over syntax nodes in the opened text file to see the appropriate

rust code that it refers to and the rust editor will also highlight the proper

text range.

If you trigger Go to Definition in the inspected Rust source file,

the syntax tree read-only editor should scroll to and select the

appropriate syntax node token.

# Profiling

We have a built-in hierarchical profiler, you can enable it by using `RA_PROFILE` env-var:

```

RA_PROFILE=* // dump everything

RA_PROFILE=foo|bar|baz // enabled only selected entries

RA_PROFILE=*@3>10 // dump everything, up to depth 3, if it takes more than 10 ms

```

In particular, I have `export RA_PROFILE='*>10'` in my shell profile.

We also have a "counting" profiler which counts number of instances of popular structs.

It is enabled by `RA_COUNT=1`.

To measure time for from-scratch analysis, use something like this:

```

$ cargo run --release -p rust-analyzer -- analysis-stats ../chalk/

```

For measuring time of incremental analysis, use either of these:

```

$ cargo run --release -p rust-analyzer -- analysis-bench ../chalk/ --highlight ../chalk/chalk-engine/src/logic.rs

$ cargo run --release -p rust-analyzer -- analysis-bench ../chalk/ --complete ../chalk/chalk-engine/src/logic.rs:94:0

```

# Release Process

Release process is handled by `release`, `dist` and `promote` xtasks, `release` being the main one.

`release` assumes that you have checkouts of `rust-analyzer`, `rust-analyzer.github.io`, and `rust-lang/rust` in the same directory:

```

./rust-analyzer

./rust-analyzer.github.io

./rust-rust-analyzer # Note the name!

```

Additionally, it assumes that remote for `rust-analyzer` is called `upstream` (I use `origin` to point to my fork).

Release steps:

1. Inside rust-analyzer, run `cargo xtask release`. This will:

* checkout the `release` branch

* reset it to `upstream/nightly`

* push it to `upstream`. This triggers GitHub Actions which:

* runs `cargo xtask dist` to package binaries and VS Code extension

* makes a GitHub release

* pushes VS Code extension to the marketplace

* create new changelog in `rust-analyzer.github.io`

* create `rust-analyzer.github.io/git.log` file with the log of merge commits since last release

2. While the release is in progress, fill-in the changelog using `git.log`

3. Commit & push the changelog

4. Tweet

5. Inside `rust-analyzer`, run `cargo xtask promote` -- this will create a PR to rust-lang/rust updating rust-analyzer's submodule.

Self-approve the PR.

# Permissions

There are three sets of people with extra permissions:

* rust-analyzer GitHub organization **admins** (which include current t-compiler leads).

Admins have full access to the org.

* **review** team in the organization.

Reviewers have `r+` access to all of organization's repositories and publish rights on crates.io.

They also have direct commit access, but all changes should via bors queue.

It's ok to self-approve if you think you know what you are doing!

bors should automatically sync the permissions.

* **triage** team in the organization.

This team can label and close issues.

|